Wat u kunt verwachten:

- Een demo van 20 minuten met een expert in onze oplossingen

- Een gesprek met een expert over uw behoeften en doelen

- Geen druk, geen verplichting

VERTROUWD DOOR MEER DAN 68.000 BEDRIJVEN WERELDWIJD

Geïnteresseerd in een gratis proefperiode?

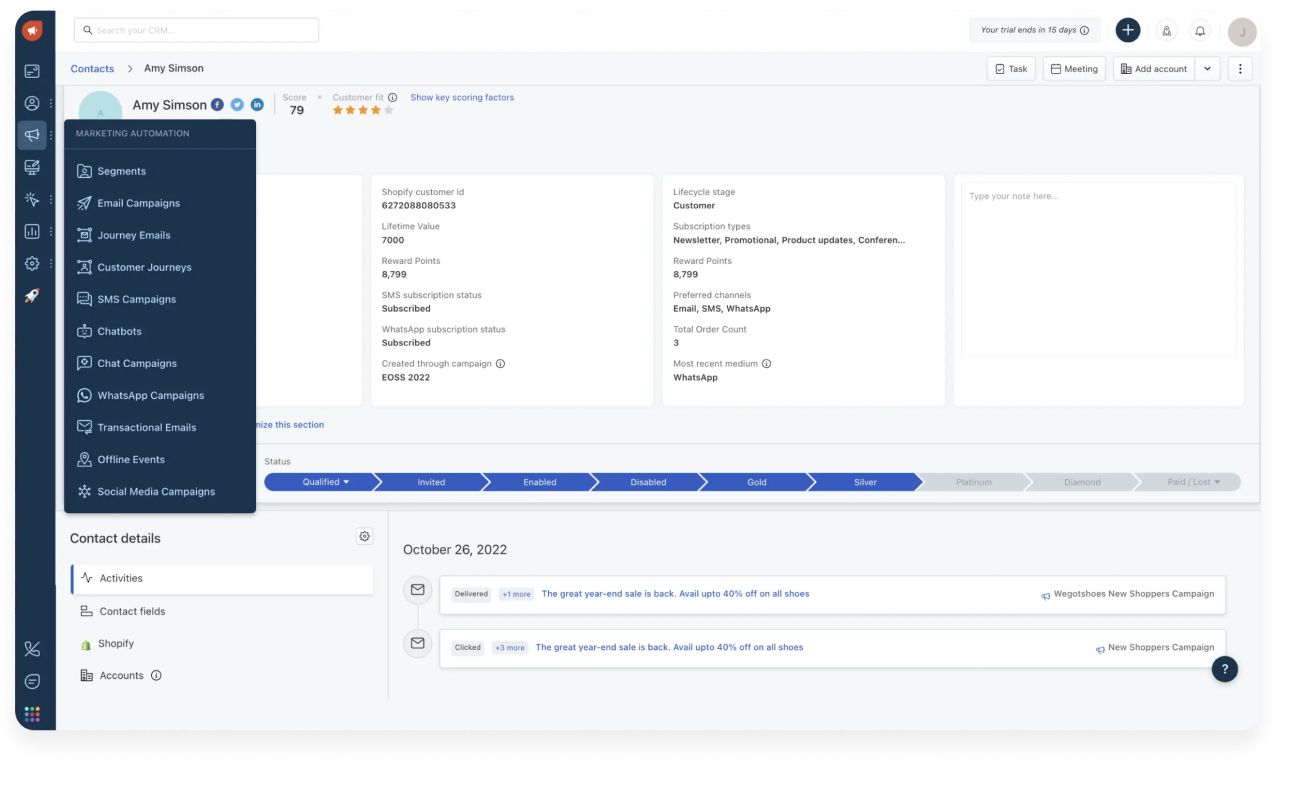

Probeer nu Freshmarketer met een gratis proefperiode van 14 dagen. Volledige toegang. Geen creditcard nodig.